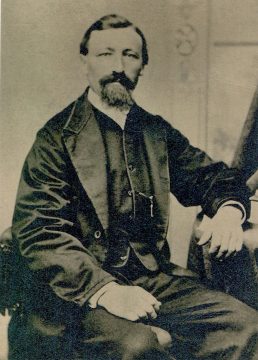

Soren Pederson

Database Record Change Request

| Name at Enlist | Soren Pederson |

| Birth Name | Sören Pederson |

| Other Names | Sören Pederson, Soren Peterson, Pedersen |

| Lived | 27 Nov 1834 – 19 Jan 1911 |

| Birth Place | Eskilstrup, Sjæland |

| Birth Country | Denmark |

| Resident of Muster-In | Neenah, Winnebago County, WI |

| Company at Enlistment | K |

| Rank at Enlistment | Private |

| Muster Date | 16 Feb 1864 |

| Cause of Death | Pneumonia |

| Death Location | El Centro, Imperial County, CA |

| Burial Location | Fort Howard Memorial Cemetery, Green Bay, Brown County, WI |

| Mother | Karen Marie Hansdatter |

| Mother Lived | 1807-1851 |

| Father | Peder Sorensen |

| Father Lived | 1806-1879 |

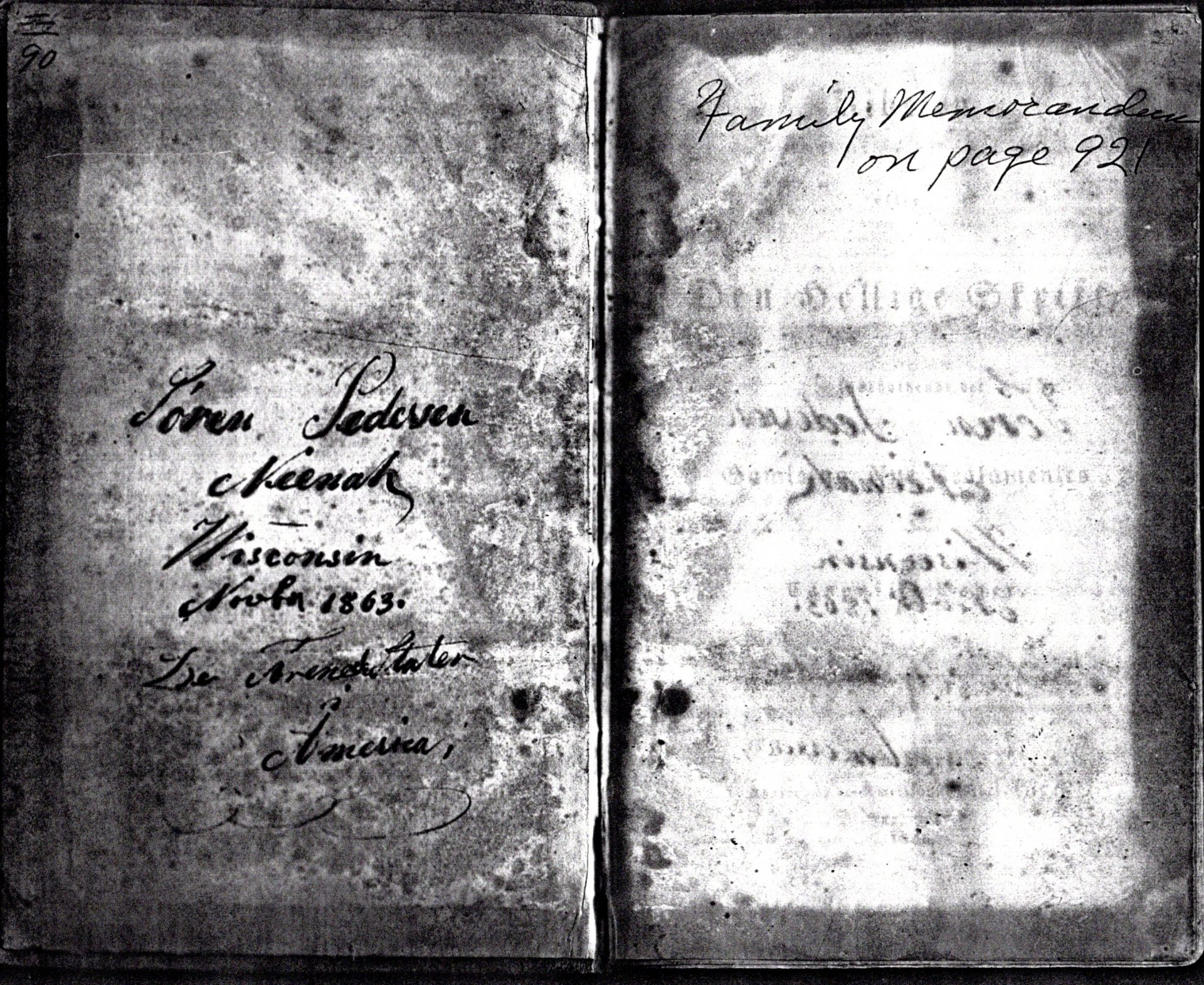

| Immigration | 1863 |

| Spouse | Dorthe Sophie Pedersdatter/Dorothea Larson |

| Spouse Lived | 21 Oct 1835-25 Jan 1911 |

| Married On | 15 Oct 1866 |

| Marriage Location | New York, New York |

Before leaving Denmark, Sören Pederson underwent 18 months of military training. After arriving in Wisconsin he worked as a farm laborer for a season. He then was enlisted in Company K of the 15th WI by John A. Johnson (brother of the 15th’s Lieutenant Colonel Ole C. Johnson) on January 23, 1864, for a three-year term of service. Company K called itself “Clausen’s Guards” in honor of the 15th’s first Chaplain, Claus L. Clausen. Sören was mustered into Federal service as a Private (Menig) on February 16, 1864, at Camp Randall near Madison, Dane County, WI. At the time he was 29 years old. His residence was recorded as East Troy, Walworth County, WI, but he had been living in Neenah, Winnebago County, WI.

After a month at Camp Randall learning to be a soldier, Private Pederson left there on March 24, 1864 to join Company K and the 15th WI, which had departed Madison two years earlier. He caught up with them on March 31, 1864, at Strawberry Plains, near Knoxville, TN. Shortly after arriving, he caught a cold and was sent to a convalescent camp near Knoxville, where he spent a month recovering. He rejoined the 15th at the beginning of General William T. Sherman’s campaign to capture Atlanta, GA. Pederson’s first combat came at Rocky Face Ridge, GA ,where on May 8, 1864, the 15th helped capture a part of the ridge. In a 1910 memoir dictated to his son, Sören described the following incident at Rocky Face Ridge:

“…the man who I relieved had built up a little fortification of the loose stones lying about and said, as I came up, that he would leave me his fort. While sitting behind this, a negro came along with coffee for us and while I was drinking it he said, “Let me take your gun. I can see a rebel up among the stones.” So he took the gun and taking deliberate aim, fired. “Oh I hit him alright,” he said. He evidently left some impression, for a moment later two or three balls [bullets] came whizzing by, some hitting the stones of my fort and one hitting a tree trunk just above my head. The negro had taken the precaution to step behind the tree before firing. My next neighbor, a tall Norwegian, was of a different temperment. Stepping out into the open and holding up his cup of coffee, he called out,”Hey you rebels, if you want any coffee come down. Better be quick about it for it will soon be gone.” Just then a bullet hit him square in the breast and he fell dead.”

Private Pederson next saw action at the Battle of Resaca, GA, from May 14-15, 1864. In his memoir he described what happened during the Federal attack on May 14th:

“About 4 o’clock we were ordered forward but so terrific was the musketry and artillery firing the moment we moved out into the open that we were speedily withdrawn. While in the firing line, I felt a sharp pain on the top of my head and taking off my hat found two bullet holes through it from front to back. Putting my hand up on top of my head I found it bleeding. I had received a scalp wound and realised that it would have been all up with me had I been a few inches taller.”

On May 27, 1864, Private Pederson fought in the Battle of Pickett’s Mill, GA, which is often referred to as the Battle of Dallas or New Hope Church. At 4:00 PM that afternoon, the 15th was ordered forward to capture the enemy’s entrenchments. They charged right up to them, but were unable to get in. They then lay down about 15 yards away and exchanged fire with the Confederates for nearly five hours. When it got dark around 9:00 PM, they were finally ordered to retreat. As they began to withdraw, the enemy suddenly charged. The 15th was virtually out of ammunition and unable to effectively resist the attack. Many of its soldiers were captured, including Private Pederson, who described what happened in his memoir:

“In the flash of a gun I saw two rebels before me with guns pointed at me, and one said, “Throw down your gun.” I had loaded it with powder and ball and cocking it, had reached for a percussion cap but found them all gone when the order came to retreat. I moved back with finger on trigger when I met these rebels and it flashed through my mind that I would shoot the one and catch the other’s gun with my bayonet. I had practiced this trick in my military training so often that I knew I could carry it out. Already my finger was closing on the trigger when I remembered there was no cap on the gun, and I threw it on the ground and marched off a prisoner…Had I had a percussion cap I should at least have met with death instead of imprisonment, which I felt would be preferable, judging from what I had already heard of prison life in the south. I was yet to learn that it was much worse than I had imagined.”

After being captured, Private Pederson was marched with other prisoners to Marietta, GA. In his memoir, Sören described how a Confederate officer searched him and the others, confiscating their money and valuables:

“I saw no use in protests or opposition so when he reached me I pulled out my bill book [wallet] and handed it to him. He opened it, saw the Confederate [five dollar] bill on top, raised one edge of it, noting the green backs [U.S. dollars] below, closed the book and handed it back to me…I [am] inclined to think that my readiness to hand over the book together with his finding the Confederate bill on top of the others lead him to believe that I was in sympathy with the south. At any rate I was permitted to take into prison what money I had with me while the rest were deprived of everything of value that could be found on their persons…If it had not been for the money I brought in with me I never would have escaped alive from Andersonville.”

From Marietta, Private Pederson was taken to the infamous Andersonville Prison Camp in GA. There he suffered unbelievably in the overcrowded filth of the prison. Violent thieves began to rob and kill fellow prisoners. He noted in his memoir how the lack of food and clean water resulted in his getting dysentery and, in August, scurvy:

“There was scurvy in the prison when I came in and this got rapidly worse as the summer heat came on. During the month of August [1864] there were more than a hundred dying [of it] every day…In the early stage of the disease they were able to walk around but the flesh was dropping off the toes. Later the disease worked up to the knees and then they were usually unable to get around.”

With his money gone, and barely able to walk, Sören became convinced that he was about to die. A fellow Danish prisoner told him to eat raw Irish potatoes to control the scurvy. Soren traded his broken pocket watch for several, which suppressed the scurvy and saved his life. However, in his memoir he described how the situation in Andersonville continued to deteriorate:

“As the days wore on our misery increased. More prisoners were constantly brought in and those who were there became more emaciated. Their clothes were wearing out and the majority went around in rags and some had scarcely anything on at all. The food became worse and the prison more and more filthy. The swamp between the hills on both sides of the stream [the only fresh water source for the prisoners] became nothing but a bog of filth with maggots. The heat became unbearable.”

Finally, at the beginning of September, 1864, Private Pederson was removed from Andersonville. It was probably about this time that he was mistakenly recorded as having died there on September 5, 1864. This error appears in the 15th’s official roster and in both Buslett’s and Ager’s post-war regimental histories. Private Pederson was shipped to Charleston, SC. There he and many other Andersonville prisoners were held in an open field near the city, from which they could see Union shells exploding over Charleston. One night Sören snuck past the guards and spent a day searching the area for an escape route. Unable to find one, he returned undetected to the field that night. He noted the following act of charity in his memoir:

“The women of Charleston often came out bringing bread for the prisoners, but the inhuman guards refused to let them come over and give it to us. So they often stood back of the guards and threw it in among us.”

In late 1864 the prisoners were sent to Florence, SC. While there Sören befriended one of the prison guards, Sergeant Wilson. He was a Dane from Copenhagen who claimed to have been forced into the Confederate Army, but was tired of the war and wanted Sören to help him desert. Sören was almost too weak to walk, so Wilson arranged for him to live in a tent outside the prison and get extra food. The prisoners and guards were later transferred to Charlotte, NC. A week later Wilson deserted, taking Sören with him. After a day on the run, Sören was too exhausted to continue and Wilson reluctantly went on without him. Sören soon gave himself up and was returned to the prison in Charlotte to a fate that he described in his memoir:

“I was taken before the Captain of the Guards and thoroughly questioned…He said they would let me off this time with some punishment and ordered Sergeant Jackson to take me out and hang me by the thumbs. This was a most cruel punishment for a rope was tied around a person’s thumbs behind his back and fastened above and pulled up till the poor fellow just barely touched the ground with his toes and left there for an hour. Jackson, however, pulled me up very little so that I stood with my full weight on the ground…Jackson was a Dane and I had reason to believe that he was friendly to me and that he sympathized with the north, but he never said much…Later another man told me that Jackson had begged the Captain not to shoot me.”

However, Sören was then made to witness the execution of Wilson, who had been captured:

“Of all the agonizing sights I saw in my war and prison life, this was the worst to me.”

Private Pederson recovered enough to escaped again in mid-April, 1865, at the very end of the war. In the dark he slipped onboard a Confederate troop train headed north, jumping off before it got light. He finally reached Federal troops, who told him the 15th WI was in Texas (it had actually been mustered out in February). Sören was given the choice of either going to Texas or home to Wisconsin. On his way home, Sören’s pass was stolen and he ended up penniless in Cincinnati, OH. At this point, the Civil War was over and Sören essentially walked away from the Army. He was never formally mustered out, even though he reportedly tried several times to do so in later years.

Sören Pederson then spent the next ten months working near Cincinnati, slowly recovering his health. He finally returned to Neenah, WI, in the spring of 1866. From there he went to Postenkiel, NY, sent to Denmark for his betrothed, got married, and returned to Wisconsin. From 1871 until 1910, he and his wife farmed and raised five children in Hartland, Shawano County, WI. The children were: Fred W. and Emma C. (Wilson), who were twins; Mary E.; Ella M.; and Edward H.

Sören and his wife were visiting their son Fred, a doctor practicing in El Centro, Imperial County, California, when Sören died of pneumonia. His wife accompanied his body back to Wisconsin where she died a week later.

Sources: War Story of Sören Peterson, a Danish Immigrant by Dr. Frederick W. Peterson (El Centro, California, 1920); Det Femtende Regiment, Wisconsin Frivillage [The Fifteenth Regiment, Wisconsin Volunteers] by Ole A. Buslett (Decorah, Iowa, 1894); Roster of Wisconsin Volunteers, War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865, Volume I, (Madison, Wisconsin, 1886); Danske I Kamp i og for Amerika by P. S. Vig (Omaha, Nebraska, 1917) with Pederson biographical information translated by Anders Rasmussen; and, Regimental Descriptive Rolls, Volume 20, Office of the Adjutant General State of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin, 1885); additional family information provided by Linda Peterson.